The Ultimate Guide to Middle Market Capital Formation

by Jon Wiley, Managing Director at Forbes Partners

Chapter 1

Capital Formation & Recapitalization

Middle market companies often need outside capital during some point in their lifespans and that results in a recapitalization. According to Wikipedia, recapitalization is a type of corporate reorganization involving substantial change in a company’s capital structure. Founders and owners of middle market businesses are motivated to seek a recapitalization for several reasons, including:

- Capital to fund growth organically or through M&A

- Refinancing on more favorable terms

- Capital desired by owners for retirement or to diversify their holdings

Consider a company with revenues in the $20-$200 million range. As neither an enterprise-level organization nor truly a small business, IPOs are rarely the right option. Debt or equity recapitalizations are often the answer, enabling middle market organizations to raise the funds they need to support growth, tap liquidity or restructure.

Typically, middle market companies seeking to recapitalize need to raise $10 million or more, are running profitably, and are well established as leaders in their markets. They have a growth plan in place and need capital to make it all work. In short, they may need more capital, expertise, and flexibility than banks can offer, which is where capital formation via institutional investors comes in. And it is more accessible than many founders and owners expect.

In this Guide, you’ll learn about the:

- Primary Drivers Behind Recapitalizations

- Types of Capital: Equity vs. Debt

- Difference Between Cash Flow and Asset Based Lenders

- Recapitalization Process

- The Types of Capital Investors

Ready to Discuss Securing Growth Capital?

“The capital formation market is primarily populated with private equity funds, alternative private debt funds, growth equity funds, and other sophisticated institutional investors.”

Chapter 2

Primary Drivers Behind Recapitalizations

No two companies and no two owners are alike. They all have their own needs, goals and challenges, and capital is just one part of their overall plan. For that reason, capital formation is often considered in partnership with traditional M&A, with one serving as a steppingstone to the other. Maybe the owners are not quite ready to sell the company yet, but with some growth capital they will be able to better position the organization for sale when the time is right.

There are effectively three primary motivations for any capital raise: growth, liquidity, and restructuring.

In terms of growth, capital allows the company to take advantage of opportunities as it sees them, through both acquisition as well as organic growth. Often it is as simple as addressing day-to-day concerns – maybe you have to turn down a large order that you can’t fulfill but could meet with extra staff or some new equipment. Or maybe it is time for a product upgrade to take advantage of a market opportunity, or simply a new acquisition target.

Liquidity involves either the founders taking money out of the business to diversify their holdings or to buy out earlier investors. Often new companies raise seed money from friends, family and other small investors, with the expectation that they will repay that investment within a certain amount of time. A company can outgrow these investors and have new capital and operational needs. This is an ideal time to replace early investors with new capital.

Restructuring is the least common motivation for capital formation and involves trading one capital partner or one type of capital for another. In the best circumstance this can involve finding less expensive sources of capital. In turnaround situations, this may involve finding a more flexible investor to take out current capital, likely with a more expensive option. Whatever the case, restructuring can help solidify the company’s position as it enters its next stage of growth.

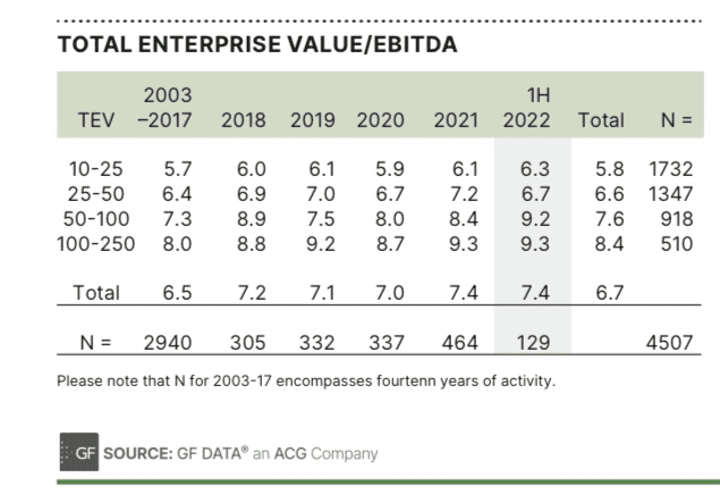

The end goal of many capital formation campaigns is to build a bigger, better, stronger company. Because, in M&A, size does matter. When you are selling a company, the larger you are the higher your exit multiple will be. This can be seen on the chart below, tracking the last nearly twenty years.

Jon Wiley is a Partner and Managing Director at Forbes Partners, where he leads the capital formation practice as well as working with both buyers and sellers of businesses.

Chapter 3

Types of Capital: Equity vs. Debt

Debt is typically the most straightforward type of capital formation. Like going to the bank to secure a loan, a debt capital transaction is often based on an EBITDA multiple with interest to be paid on top of the principal over a set period of time.

But not all debt lenders are the same. In addition to banks, mezzanine lenders can offer businesses additional financing on top of their base loans. These deals are structured as secondary loans that come in behind the bank – structured as a junior capital provider, these mezzanine lenders only get their money back after the bank in the case of a default – so they often charge higher rates as a result. Between the two extremes are lenders that will cover all of a business’ capital needs, often called unitranche lenders, for a rate that’s higher than most banks but less than a mezzanine lender will charge.

In today’s business environment, raising capital has become a complex challenge. Companies seeking funds often face various issues simultaneously. Economic uncertainties, higher interest rates, difficulties in obtaining bank loans, and challenges in selling a business at the right price are common hurdles. Navigating these challenges requires a careful and strategic approach.

Jon Wiley, Partner & Managing Director, Forbes Partners

One of the trade-offs for borrowers in different types of debt transactions is cash flow. When borrowing from a bank, a business will typically be on a set amortization schedule where they will be paying interest throughout the life of the loan and paying down a portion of the principal every year. Whereas some non-bank lenders will just charge the interest, or a very limited principal paydown, over the life of the loan. The expectation is that the loan will drive growth and can be refinanced and paid in full within the term of the loan.

That is one of the primary benefits of working with a non-bank lender. While the interest rate may be higher, more of the capital that you raise can be spent on growth, rather than simply paying down the loan. As the business grows more options become available to pay off the balance when it is due or even earlier.

Equity capital works differently. By investing in the future of the company alongside ownership, equity investors are staking their own financial interest in the organization’s growth and success. They can do that either as majority investors, buying the company outright, or as minority investors who give up that control in exchange for some other protections.

The outcome of these types of equity transactions can vary based on the structure of the investment. Minority investors might have a seat on the board and some veto power over major company decisions – such as forbidding ownership from selling the company or raising additional capital without their approval – but without the total control they would enjoy as majority owners. Often these types of transactions are structured as Preferred Equity investments where the minority investors get their money back first in the event of an exit or other liquidity event, with the remainder split between the owners and any other investors on an agreed-upon percentage.

Want to determine the best capital formation or recapitalization options for your business?

Chapter 4

Insight into the Capital Formation Process

At its core, a capital formation campaign is very similar to the M&A process that a company would go through if its founders were looking to sell the company. It starts with choosing an advisor and sharing the details of the business with them – what their existing ownership structure looks like, who is on their current capital table, what percentage of the company each principal owns, and what the different owners’ goals and expectations are for the transaction.

Then, the process turns to how the capital will be used. Is there a specific acquisition target that is already lined up or is the company considering an acquisition search? Does the company need to hire immediately to maintain its growth momentum or is it looking ahead to future needs? Or do the owners just want the flexibility to take some money out of the business or buy out one of the partners? The intended use of the funds can impact the type of recapitalization that an advisor will recommend and what types of investors they will work with.

From there, it’s time to determine what the ideal capital structure needs to be to accomplish those goals. Some companies prefer to pay a higher interest rate to a debt lender in order to preserve equity in the company, while others would rather bring in a partner who could also offer other expertise beyond capital. Often, the financial statements help determine the answer. If there is no room for any more debt on the balance sheet, an equity transaction might be the only option.

Once the objective is determined, the next steps include assembling the marketing material to promote the opportunity, collecting the confidential financial information that prospective investors will need to see, and putting together a list of target institutional investors to contact. Those that are interested will have phone calls with the team, review the company’s financials and other information and offer term sheets for the transaction. Sometimes these term sheets can be meaningfully different, leaving the business’ owners to choose which deal is the best fit for their company.

Once the final terms have been agreed upon and all legal due diligence completed, a closing date is set, and funding is completed. Depending on the complexity of the transaction, the entire process can take between three and nine months from start to finish, with debt deals traditionally being shorter and equity deals taking longer to close.

Download the Guide

Ultimate Guide to Middle Market Capital Formation

Getting bank financing has become tough in the current climate. Many companies find it challenging to secure new loans, and some are even losing their existing ones. The situation is exacerbated by increasing interest rates, which means the bank debts that were once manageable could now be limiting the company’s cash flow.

Jon Wiley, Partner & Managing Director, Forbes Partners

Chapter 5

The Difference Between Cash Flow and Asset-Based Lenders

Lenders generally focus on either a company’s cash flow or its assets. As the name implies, cash flow lenders work based on how much money the company has coming in and how much it makes in a set period of time. Asset-based lenders, on the other hand, look at your collateral instead. Does the company own its own real estate? How many physical assets does it have on the balance sheet? Are there contracts in place that they could lend against?

Asset-based capital can be easier to secure but it is often more expensive. These loans are generally for companies that don’t have consistent or predictable cash flow. The lenders will still review the company’s operation when underwriting the loan but they are ultimately relying on the ability to sell the assets used as collateral if something goes wrong,

Working with an asset-based lender can be fairly straightforward and quick. The lender will typically advance you a percentage of the appraised value of the assets that they are willing to lend against.

Cash flow lenders, on the other hand, take a more holistic view of the company overall. They consider your EBITDA, pipeline, Total Enterprise Value, and other metrics to determine an amount that they are comfortable lending. Often these lenders work in tight segments of the market and know what growth companies in their verticals look like, using that experience to back up their decisions.

Chapter 6

The Types of Capital Investors

Unlike traditional M&A, where both financial buyers as well as strategic acquirers are common, the capital formation market is primarily populated with private equity funds, alternative private debt funds, growth equity funds, and other sophisticated institutional investors. The record amount of capital raised in the past several years is being diversified across a number of different investment strategies. For instance, many traditional private equity funds have also raised growth funds and debt funds to support growth companies at different stages and with different needs.

Family offices are another segment of this investor market. Also, common participants in M&A, family offices act a lot like private equity funds but instead of raising money from limited partners and other investors their capital typically comes from just a handful of individuals, often a founder or CEO who has gone through a significant exit and is now investing their money in other companies.

Finding the right capital partner can be as important as finding the right capital structure. The right partner matters because institutional investors can bring a lot more to the table than just capital. They also have experience building great companies, have other portfolio companies in their network to whom they can facilitate introductions, and can serve as a sounding board to help CEOs brainstorm new ideas, and are proficient at analyzing and completing acquisitions.

Companies often work very well with one structure while growing into $50 million organizations. But the road from $50 million to $200 million and beyond may take a different skill set and involve different complexities and needs. This is where sophisticated institutional investors can be invaluable, offering back-office support, connections, and advice to help the company grow.

Institutional investors make their living looking at acquisition targets and analyzing businesses. One of the most common areas for fast growth is through acquisition of a similar company. This might be a current competitor, supplier or another company that offers synergies. Having a capital partner with experience in analyzing and negotiating these acquisitions, as well as financing available to fund them, is a major benefit to raising institutional capital.

Finally, it is important not to overlook the company’s vision and culture when considering new capital. Asking the right questions of prospective partners is key. How do they react if things don’t go according to plan? Do they agree with the current vision, or would they like to pursue other avenues? What is their ultimate goal with the investment?

The number of deals with M&A firms are increasing. Companies that are not ready to sell are taking advantage of minority and structured deals with a growth partner. Consequently, more money is being raised by funds – both for private debt and minority recaps.

Jon Wiley, Partner & Managing Director, Forbes Partners

Talk with Forbes.

Exceptional companies need an exceptional investment bank. Forbes Partners has the expertise to exceed expectations and achieve optimal outcomes for you.

Forbes Partners is an award-winning middle market investment banking firm focused on driving maximum value to clients. We help our clients restructure debt or recapitalize their business to meet evolving needs. Many owners desire liquidity while still maintaining control of their businesses. Forbes Partners can help them achieve their goal. Our experienced bankers think strategically about value creation — we are market makers, and our clients expect nothing less.